Black Blizzards of the Dust Bowl

– ‘The End of the World Is Coming!’

It was a tectonic shift of two eras. The great age of the bison and the free Indians who hunted

them gave way to the Manifest Destiny with its own kind of stampede – the surge of white settlers

on the Great Plains. Hunting grounds emptied of bison gave way to farms that would be

emptied of crops from dust storms caused by unsustainable agricultural practices, and both

disasters bore the stain of human causation – ignorance, greed and misplaced faith. And out

of both arose the resilience and inventiveness of the American spirit in overcoming adversity

and adapting to change.

The Dust Bowl is widely considered to be the greatest man-made ecological catastrophe in

the United States. Ideas, we know, have consequences, and Manifest Destiny was one that

would eventually and unintentionally wreak havoc on the heartland.

In simplest terms, the phrase conveyed a belief that expansion of the nation’s boundaries to

the Pacific was God-ordained, inspiring many adventurers to leave the crowded East for the

West. Under the Homestead Act of 1862, the government gave up to 160 acres of free land

to farmers who promised to live on it, improve the land and farm for five years or more.

Among the ranks of settlers seeking greater freedom and land ownership were whites,

African-Americans and European immigrants. The prospect of new beginnings on a vast new

frontier fanned dreams into reality. Railroads replaced covered wagons, making widespread

settlement possible, and “in the 1880s and ‘90s farmers began to crowd the ranchers, and

wheat began to replace cattle,” according to Britannica. Weather and climate on the semi-arid

plains is highly variable, with seasons of drought and rain, but the first wave of settlers came

in years of plentiful rain.

Migrating from Tennessee, these four people homesteaded in Nicodemus, Kansas.

(National Park Service)

Sod house in North Dakota built by Norwegian settlers, 1898.

(Wikipedia)

An offspring of the notion of a divine imperative to drive westward expansion is seen in another

popular and unfortunate slogan: “Rain follows the plow.” It also served to “dispel the

rumor that the middle of America was not good for farming,” as explained in a homestead

blog. The slogan was coined by Charles Dana Wilber in his 1881 book The Great Valleys and

Prairies of Nebraska and the Northwest:

“Suppose (an army of frontier farmers) 50 miles, in width, from Manitoba to Texas, could acting

in concert, turn over the prairie sod, and after deep plowing and receiving the rain and

moisture, present a new surface of green growing crops instead of dry, hard baked earth covered

with sparse buffalo grass. No one can question or doubt the inevitable effect of this

cooling condensing surface upon the moisture in the atmosphere as it moves over by the

Western winds. A reduction of temperature must at once occur, accompanied by the usual

phenomena of showers. The chief agency in this transformation is agriculture. To be more

concise. Rain follows the plow.”

And so they plowed, destroying 5.2 million acres of deep-rooted prairie grass to plant corn

and the crop best suited to the region, wheat. But they didn’t know that those tall prairie

grasses were nature’s way of protecting the topsoil.

With World War I beginning in 1914, the food supply in Europe began to fall sharply, bringing

food grown in the United States into high demand. The price of wheat doubled. One writer

said farmers thought they’d found “wheat heaven.”

Fast forward to the early 1920s. Farmers are taking advantage of innovative ways to increase

their production. They’re buying (frequently on credit) the burgeoning new technologies of

labor-saving equipment such as mechanized tractors and threshing machines, and seeing

impressive increase of their agricultural output.

Then in 1929 the Great Depression hits, and wheat prices drop from $2 a bushel to 40 cents.

Farmers begin to “tear up even more prairie in sod in hopes of harvesting bumper crops,”

says Ken Burns in his landmark documentary The Dust Bowl. As prices continued to plummet,

these “suitcase” farmers, hoping to make a quick buck, packed up and left. The fields they

abandoned “now lay naked and exposed.”

Wheat field on Dutch Flats near Mitchell, Nebraska, Farm of T.C. Shawver, 1910.

(U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

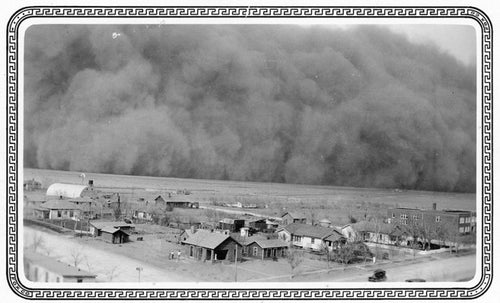

As you can see, a perfect storm is gathering and growing in year after year of prolonged drought – nearly the entire decade of the 30s – and with the drought came dust, huge, rolling, rising walls of dust across the Great Plains smothering cattle, cars and even people. The dust storms lasted from one hour to three and a half days. Jennifer Robinson points out the terrible effects on people and animals: “The dust was beginning to make living things sick. Animals were found dead in the fields, their stomachs coated with two inches of dirt. People spat up clods of dirt as big around as a pencil. An epidemic raged throughout the Plains: they called it dust pneumonia.”

The worst storm came on April 14, 1935, a day called Black Sunday. With a cold front from Canada colliding with warm air over the Dakotas, the temperature plunged more than 30 degrees, and the raging wind created “a dust cloud that grew to hundreds of miles wide and thousands of feet high as it headed south,” according to the History newsletter.

The black blizzard rampaged in Colorado and Kansas, and unleashed its full fury in the Texas

and Oklahoma panhandles.

In his Pampa, Texas home, folksinger Woody Guthrie, said, “You couldn’t see your hand before

your face.” The apocalyptic scale of the disaster inspired him to write several “Dust Bowl

Ballads,” which you can listen to on YouTube. An estimated 300,000 tons of topsoil were displaced,

with dirt flying all the way to the East Coast. No wonder the decade was named “The

Dirty Thirties.” All totaled for the year 1935, 850 million tons of topsoil blew away. “’Unless

something is done,’ a government report predicted, ‘the western plains will be as arid as the

Arabian desert.’”

Car chased by a black blizzard in Texas panhandle, March 1936.

(Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Library of Congress)

In an article in the New Republic, Avis D. Carlson gives a graphic picture: "People caught in

their own yards grope for the doorstep. Cars come to a standstill, for no light in the world can

penetrate that swirling murk…. The nightmare is deepest during the storms. But on the occasional

bright day and the usual gray day we cannot shake from it. We live with the dust, eat it,

sleep with it, watch it strip us of possessions and the hope of possessions."

One woman, interviewed in Burns’ The Dust Bowl, exclaims, “We saw this cloud coming in

black, black dirt, and I’ll never forget what my grandmother said – she said, “You kids run and

get together. The end of the world’s coming!”

Dust storm in Rolla, Kansas on Black Sunday, April 14, 1935

(Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs)

Aftermath of dust storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, April 1936

(Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Courtesy Library of Congress)

With lands and livelihoods destroyed, farmers and their families left the Plains in droves, migrating from Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado, Kansas and New Mexico hoping to find work farther west. In all some 2.5 million people left the Dust Bowl region, with about 300,000 of them headed for California looking for jobs. You can listen to soul-stirring portions of their stories and songs, recorded in 1940 by Charles Todd and Robert Sonkin. Todd was commissioned by the Library of Congress to travel throughout California’s central valley and produce oral histories of the refugees, the region that’s the setting for John Steinbeck’s epic novel The Grapes of Wrath.

This the region of the affected states. The Dust Bowl area is in brown;

the areas affected are in yellow. The red mark is Frederick, Oklahoma.

(The Legal Genealogist)

"Broke, baby sick, and car trouble!" Missouri migrant family's jalopy

breaks down near Tracy, California.

(Photo by Dorothea Lange, 1937, Library of Congress)

Under Roosevelt’s New Deal, a series of measures was launched to aid suffering Americans

and prevent future ecological disasters, though the effects weren’t immediate. Programs like

the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the Soil Conservation Service, the Taylor Grazing, and

the Shelterbelt Project helped farmers to become self-sustaining; they enriched and protected

the soil, planted two million trees and fought wind erosion. The Civilian Conservation

Corps and Works Progress Administration created jobs for millions of unemployed Americans.

An enduring FSA program that brought the Dust Bowl and the Depression before the eyes of

Americans and continues to do so was “a visual encyclopedia of American life,” as described

by Roy Stryker. As the administrator, he hired a team of eleven photographers to take pictures

of people everywhere in America, but especially rural America. These high-quality photographs

are found on multiple internet sites and are in the public domain.

An Oklahoman boy during a dust storm, 1936

(Photo by Arthur Rothstein, Wikipedia)

We are happy for you to use the content on our historical pages if you will reference the source, www.BenjaminLeeBison.com and send an email to explain your intended use to Jessi at jessi@BenjaminLeeBison.com

Sources

Dietz, John L. and Elwyn B. Robinson, "Great Plains." Encyclopedia Britannica, November 17, 2020.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Great-Plains

“Homestead Myth: The Rain Follows the Plow,” October 16, 2009. Homestead Congress Blogspot.

http://homesteadcongress.blogspot.com/2009/10/homestead-myth-rain-follows-plow.html

Suzanne U. Clark, “When ‘Wheat Heaven’ Turned to Dust, March 13, 1998, God’s World News.

“The Dust Bowl,” Legacy, PBS. http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/dustbowl/legacy/

“Farming in the 1920s,” Wessels Living History Farm. https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe20s/machines_

01.htm

32

Jesse Greenspan, “What Happened on Black Sunday?” April 13, 2020. https://www.history.com/news/

remembering-black-sunday

“Lost and Found Sound: Voices from the Dust Bowl,” NPR, July 28, 2005. https://www.npr.org/

2005/07/28/3187034/voices-from-the-dustbowl#:~:

text=Voices%20from%20the%20Dust%20Bowl%20In%201940%2C%20Charles%20Todd%20

and,music%20of%20Dust%20Bowl%20refugees

Woody Guthrie, Dust Bowl Ballads, 1940. Woody Guthrie - Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues.AVI – YouTube

Jennifer Robinson, “American Experience: Surviving the Dust Bowl,” January 29, 2019. KPBS-TV. https://

www.kpbs.org/news/2009/nov/13/american-experience-surviving-dust-bowl/

Judy Russell, “Dust Bowl Images We Can Use,” November 21, 2012, The Legal Genealogist.

33

Want to learn more about the history of bison in North America?

Join our newsletter for articles, facts and news on the American bison